The Role of Macronutrients in Exercise

This article offers a concise yet comprehensive overview of the three primary macronutrients: protein, fats, and carbohydrates. It highlights the crucial roles each macronutrient plays in fueling the human body to optimize athletic performance. Additionally, practical recommendations for the appropriate consumption amounts of each macronutrient are provided, empowering readers to make informed choices regarding their dietary intake.

NUTRITION

7/9/20248 min read

Food is composed of a combination of protein, fats, and carbohydrates. These are called macronutrients, which means that the nutrient is needed in large quantities for normal development and growth [1]. Macronutrients are the body’s source of calories and energy that fuel the various life processes inside the body [1].

Protein

Protein is a crucial macronutrient that plays important roles in endurance and resistance training exercise. Both modes of exercise stimulate muscle protein synthesis, which is the process in which the body turns amino acids into muscle. When digested, protein breaks down into amino acids, which are used by the body to repair and rebuild muscle [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. It is important to understand the difference between essential and nonessential amino acids. The body cannot produce essential amino acids, and there are nine of these essential amino acids that must be consumed in the diet. Conversely, nonessential amino acids can be produced by the human body and do not need to be consumed in the diet. Generally, all nine essential amino acids can be found in animal products, which are complete protein sources. Plant foods, however, are incomplete protein sources because they are low in one or more of the nine essential amino acids. Plant foods can become complete protein sources by combining complementary incomplete plant proteins that together can provide all the essential amino acids. Some excellent combinations include grains-legumes (e.g., rice and beans), grains-dairy (e.g., pasta and cheese), and legumes-seeds (e.g., falafel) [1].

Protein and Athletic Performance. Protein balance is measured in terms of a nitrogen balance, which is a measure of the nitrogen consumed (from dietary consumption of protein) and the nitrogen excreted (from protein breakdown) [3]. A positive nitrogen balance is the state in which the body produces more protein than it breaks down, called anabolism, and this occurs in response to resistance training when overloading the muscle [3]. However, just because an athlete consumes a high protein diet does not necessarily mean that they will be in a positive nitrogen balance and experience muscle growth [3]. Protein consumption beyond recommended amounts is unlikely to result in further muscle gains because the body has a limited capacity to use amino acids to build muscle [3]. Most studies suggest that there is a threshold effect of 1.6 to 1.7 g/kg (0.7 to 0.8 g/lb.) protein. Beyond that amount, there is no further increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis. In fact, consumption of protein beyond 1.6 to 1.7 g/kg (0.7 to 0.8 g/lb.) promotes increased amino acid breakdown that may be converted to carbohydrate or fat [1, 3]. Excess protein intake is unlikely to result in further muscle gains because of the body’s limited capacity to utilize amino acids to build muscle [4].

Protein metabolism becomes more efficient with exercise training, which supports the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) assertion that athletes do not have increased protein needs compared to the more sedentary population [4]. Muscle protein synthesis is further enhanced if protein is consumed around the time of exercise training. Research indicates meals and snacks consumed throughout the day, particularly foods consumed before, during, and after exercise, should be a combination of carbohydrates and protein at approximately a 3:1 ratio to encourage a positive nitrogen balance, which ensures muscle synthesis, hydration, and adequate energy to sustain exercise [4]. Consumption of protein immediately after exercise (within 15 to 30 minutes) helps in the repair and synthesis of muscle proteins [4]. Furthermore, it is recommended that 6 to 20 grams of protein be consumed with 30 to 40 grams of carbohydrates within 3 hours’ post-exercise as well as immediately before exercise to encourage muscle resynthesis [4]. Research indicates that as little as 5 to 10 grams of protein consumed immediately after exercise can promote optimal muscle repair [4]. Protein consumption with the intake of water post-exercise also helps to restore hydration. Carbohydrates are important to pair with protein. If only protein is consumed without sufficient carbs to provide the body’s energy needs, then muscle synthesis may be compromised [4].

Protein Recommendation

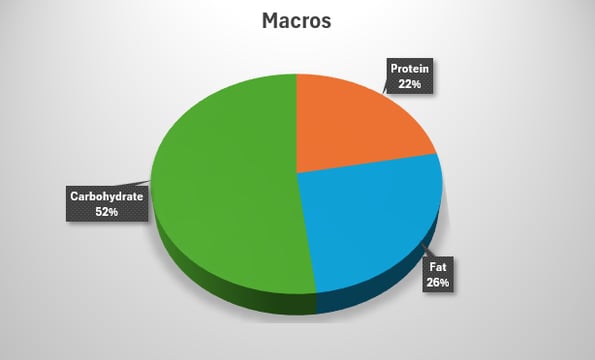

Per the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR), which was developed by the Institute of Medicine, protein should account for 10-35 percent of total daily calories [1, 3, 4].

The daily minimum for most healthy individuals is 0.8 g/kg (0.36 g/lb.) of body weight; however, athletes may need anywhere from 1.2 to 1.7 g/kg (0.5 to 0.8 g/lb.) of body weight per day [1, 3, 4].

Recommended protein intakes are best met through diet, though many athletes do turn to whey- or casein-based protein powders and other supplements to boost protein intake [3].

Fats

Fats serve many critical functions in the body, and dietary fat is necessary to maintain good health and hormonal balance. There are four categories of fats known as trans fats, saturated fats, monounsaturated fats, and polyunsaturated fats. Trans fats and saturated fats lead to clogging of the arteries, increased risk for heart disease, and a myriad of other problems [1]. Mono- and polyunsaturated fats are good kinds of fats, which are heart-healthy and excellent sources of essential nutrients. They lower bad low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and raise good high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Fats and Athletic Performance. There is no evidence for performance benefit from a very low-fat diet (<15 percent of total calories) or from a high-fat diet [1, 3]. Omega-3 fatty acids provide a variety of performance-enhancing effects for athletes, such as increasing muscle growth, improving strength and physical performance, reducing exercise-induced muscle damage and delayed-onset muscle soreness, combating negative immune effects of intensive training, strengthening bones, improving heart and lung function, and enhancing cognitive function [6].

Fat Recommendation

Per the AMDR, fats should account for 20-35 percent of total daily calories [1, 3, 4].

Consume fewer than 10 percent of calories from saturated fat [4].

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommends that 15-20 percent of caloric intake come from monounsaturated fatty acids [4].

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommends that intake from polyunsaturated fatty acids comprise 3-10 percent of total caloric intake [4].

Approximately 1-2 grams per day of Omega-3, with an eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) ratio of 2:1, can improve cardiovascular function and exercise performance [6].

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are the body’s preferred energy source [1, 2, 3, 4]. In fact, healthy carbohydrates chosen in appropriate amounts and at appropriate times can benefit athletic performance, weight management, and optimal health [4]. Carbs are ideally suited to provide fuel for the body’s many metabolic functions, including that required for normal brain function [2, 4]. When carbs are readily available, the body does not need to break down protein for fuel. This protein sparing allows protein to be used to build muscle and other important body tissues and structures rather than for energy. Furthermore, carbs can be used for energy during endurance and resistance exercise and are required to efficiently break down fat. In addition, fiber, which is an important type of carb, improves digestive health and blood cholesterol levels. Carbs are broken down into simple sugar (glucose), which is easily assimilated and used in the body. This glucose is absorbed into the bloodstream and goes to power whatever cells need energy to fuel activity (sitting, walking, eating, digesting, thinking, and the like). In fact, your brain runs exclusively on glucose, and if you’re not eating carbs, you will likely experience brain fog or have difficulty concentrating [1, 2, 3, 4].

Carbohydrates and Athletic Performance. Healthy carbohydrates chosen in appropriate amounts and at appropriate times can benefit athletic performance [4]. Carbs are ranked based on their blood glucose response using the Glycemic Index (GI). High-GI foods break down quickly (causing a large glucose spike), and low-GI foods break down slower (causing a smaller glucose spike). Research suggests that a diet based on consumption of high-GI carbs promotes greater glycogen storage following strenuous exercise [1]. Overall, high-GI glucose-rich foods are good for refueling and athletic performance [1].

A small snack before strenuous or prolonged exercise will help to optimize the training session. The food should be relatively high in carbohydrate to maximize blood glucose availability, relatively low in fat and fiber to minimize gastrointestinal distress and facilitate gastric emptying, moderate in protein, and well-tolerated by the individual [1]. During extended training sessions, exercisers should consume 30 to 60 grams of carbohydrate per hour of training to maintain blood glucose levels [1]. This is especially important for training sessions lasting longer than one hour; exercise in extreme heat, cold, or high altitude; and when the individual did not consume adequate amounts of food or drink prior to the training session. After exercise, individuals should focus on carbs and protein. Studies show that the best meals for post-workout refueling include an abundance of carbs accompanied by some protein [1]. The carbs replenish the used-up energy that is normally stored as glycogen in the muscle and liver, and the protein helps to rebuild the muscles that were fatigued with exercise. The amount of refueling depends on the intensity and duration of the training session, but the exerciser should eat as soon after exercising as possible, preferably within 30 minutes. This is the time when the muscles are best able to replenish energy stores, enabling the body to prepare for the next workout [1].

Carbohydrate Recommendation

Per the AMDR, carbohydrates should account for 45-65 percent of total daily calories [4].

Consume fewer than 10 percent of total calories from added sugars [1, 3, 4].

The daily minimum for most healthy individuals is 130 grams per day [4]. This is a minimum requirement based on the amount of carbs needed by the brain daily [4]. Therefore, for energy maintenance the body needs more than 130 grams per day [4].

Athletes need anywhere from 6 to 10 g/kg (3 to 5 g/lb.) of body weight per day depending on their total energy expenditure, type of exercise performed, gender, and environmental conditions, to maintain blood glucose levels during exercise and to replace muscle glycogen [1, 3, 4].

The American Dietetic Association (ADA) recommends a carb intake of 1.0 to 1.5 g/kg (0.5 to 0.7 g/lb.) of body weight in the first 30 minutes after exercise and then every 2 hours for 4-6 hours [1].

Conclusion

Active adults require conscientious fueling and refueling to maintain optimal performance and overall health. The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2005 Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) recommend that approximately 45-65 percent of calories come from carbs, 10-35 percent from protein, and 20-35 percent from fats [1, 3, 4]. Although active individuals require adequate carbs to maintain blood glucose during exercise and replace muscle glycogen expended during exercise, as well as increased protein for muscle repair, research suggests that active individuals do not need a greater percentage of calories from carbs or protein than the average population [1]. However, they can meet increased demands by a greater overall caloric intake [1].

Sources

[1] Bryant, C. X., & Green, D. J. (2017). Ace Essentials of Exercise Science for Fitness Professionals. American Council on Exercise.

[2] Efferding, S., & McCune, D. (2021). The vertical diet. Victory Belt Publishing.

[3] Muth, N. D., & Tanaka, M. S. (2013). Ace Fitness Nutrition Manual. American Council on Exercise.

[4] Muth, N. D., & Zive, M. M. (2020). Sports nutrition for health professionals (2nd ed.). F.A. Davis.

[5] Zinczenko, D., & Spiker, T. (2010). The new ABS diet: The six-week plan to flatten your belly and firm up your body for life. Rodale Press.

[6] Bertucci D R Ferraresi C 2016 Strength Training: Methods, Health Benefits and DopingBertucci, D. R., & Ferraresi, C. (2016). Strength Training: Methods, Health Benefits and Doping. Nova Science Publishers. https://eds-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzExMzQ0NTZfX0FO0?sid=b5e6955f-8aa1-4fff-906c-5bba28f3d5d2@redis&vid=1&format=EB&rid=1

Copyright © 2024-2025 AnlianFitness. All rights reserved.

Follow us on social media.

YouTube